Verbs are words which express that something has taken place over time. Verbs can refer to actions, events and states (e.g. købe ‘buy’, falde ‘fall’, and sidde ‘sit’). A sentence, in written language, is defined as a unit composed of one finite verb plus a subject. But utterances in talk-in-interaction can behave differently i.e. the verb and/or the subject can be omitted completely (see Sentences). The function of a verb is to link the syntactic and content parts of the utterances together, hereby extending their influence on all parts of a sentence. In the example below sir ‘say’ connects du ‘you’ with hva ‘what’ in the construction of the question hva sir du? lit. ‘what say you?’ in line 1 (see Clause constituents).

![SAMTALEBANK | SAM3 | OMFODBOLD | 54 ((face-to-face)) 01 LIS: hva sir du→ what say.PRS you.SG 'what are you saying' 02 KIR: jeg sir du købte alligevel småkag[er]↗ I say.PRS you.SG buy.PST after.all cookie.PL 'I say you did buy cookies after all' 03 LIS: [n ]ej 'no' 04 LIS: det har dorte gjort↘ that.N have.PRS NAME do.PPT 'dorte did'](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/3/csm_verbs_1_b2801b2838.png)

There are two types of verbs: Main verbs and auxiliary verbs. These will be described in detail in the paragraphs below. In the example above, the verbs sir (‘say’), købte (‘bought’), and gjort (‘done’) in line 1-3 show different versions and conjugations of main verbs, while har (‘has’) in line 3 acts as an auxiliary verb.

Verbs of talk-in-interaction has a similar conjugation potential as those of written language, that is they can inflect for

The verbs of talk-in-interaction differ largely from those of written language in their sound production. In short, we do not pronounce them as they are spelled out on paper. Verbs of talk-in-interaction inflect differently from the written ones, although their construction is still regular and systematic. Additionally, stress and stød greatly influence the inflection of the verbs. Finally, the placement of the verbs in talk-in-interaction also differs from that of written language.

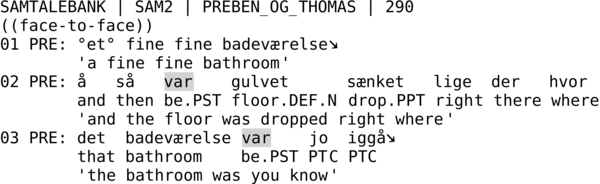

In talk-in-interaction most verbs exist in a stressed and an unstressed version, which can be quite different from one another. This so because of the so-called “stress loss”. Stress-loss has to do with “unit stress” in Danish, that is, the fact that verbs are often connected with other coherent statements as in e.g. hun ogik 'tur ‘she went (for a) walk’ or in solen ostår 'op lit. ‘the sun stands up’ (the sun rises). In both examples the symbol ‘o’ indicates lack of stress and ‘'’ indicates a stressed syllable. In the example below you can hear how var ‘was’ is both stressed and unstressed in lines 2 and 3.

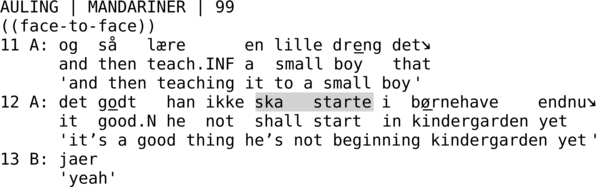

Main verbs carry the sentence’s semantic content, whereas the auxiliary verb only carries grammatical content. In the examples below the verb starter ‘starts’ thus carries the action related content. In line 2 starter ’starts’ stands alone as the sentence’s finite verb, whereas starte ‘start’ in line 12 stands as the non-finite verb of the sentence. In the latter case the auxiliary verb skal ’will’ acts as a tense indicator.

The verbs of talk-in-interaction can be divided into two types of inflections: weak and strong. Weak verbs in Danish take one of the following endings in the past tense: -de, -te or -ede as in the words arbejde-de ‘worked’, læs-te ‘read’ and vent-ede ‘waited’. Strongly inflected verbs, also called irregular verbs, are inflected without adding a suffix, e.g. drikke à drak ‘drink’ à ‘drank’. In some cases, however, for example in hang vs. hængte which both mean ‘hung’, there is an actual meaning difference at play i.e. jeg hængte jakken op ‘I hung (up) the jacket’ vs. jakken hang på knagen ‘the jacket hung on the coathook’.

Below is an overview over these differently inflected verbs. In the overview you will find: weak verbs ending in –ð (soft d) in the past tense; weak verbs ending in –d(ə) in the past tense; weak verbs with vowel lengthening as ending in the past tense, and finally the strongly inflected verbs.

The reader must take notice of the fact that we have only chosen to illustrate the forms of stressed verbs, given that the weak verbs follow the general pattern of the strong verbs, but without stress and stød. If there is an exception to this, it will be clearly indicated.

Here are some examples of different types of verbs. These are mere examples, see more in Monrad (2010).

danse – ‘dance’ | leve – ‘live’ | |||

Speech (IPA) | Writing | Speech (IPA) | Writing | |

Infinitive, strong | dans | danse | leː(ː)w | leve |

Imperative, strong | danˀs | dans | lewˀ | lev |

Present tense, strong | ˈdansʌ | danser | ˈleːwʌ | lever |

Past tense, strong | ˈdans(ə)ðð, ˈdans(ə)d | dansede | ˈle:(ː)wð, ˈleː (ː)wd | levede |

Perfect participle, strong | ˈdans(ə)ð | danset | ˈleː(ː)wð, ˈleː(ː)wd | levet |

Present participle,strong | ˈdansnə, ˈdansnn | dansende | ˈleːwnnə, ˈleːwnn | levende |

Present tense passive, strong | ˈdans(ə)s | danses | ˈleː(ː)ws | leves |

Past tense passive, strong | ˈdans(ə)ðs, ˈdansðs | dansedes | ˈleː(ː)wðs, ˈleː(ː)wds | levedes |

Stød plays an important role in the meaning of verbs in Danish talk-in-interaction. All the verbs in group 1 which can have stød, have it in the imperative form. The verbs which have stød in the infinitive form typically also have it in the other strong forms, except for the present participle. The realization of the suffixes as either [-ð] or [-(ə)d] in the past and perfect participle forms is due to regional dialectal variance.

Next is an overview of the suffixes in group 1:

Suffixes in speech (IPA) | Suffixes in writing | |

Infinitive, strong | no suffix (-ə) | -e |

Imperative, strong | no suffix | no suffix |

Present tense, strong | -ʌ | -er |

Past tense, strong | (ə)ð(ð), (ə)d | -ede |

Perfect participle, strong | (ə)ð, (e)d | -et |

Present participle, strong | -nə, -nn | -ende |

Present passive, strong | -( ə)s | -es |

Past passive, weak | -əðs, -ðs | -edes |

køre ‘drive’ | spørge ‘ask’ | |||

Speech (IPA) | Writing | Speech (IPA) | Writing | |

Infinitive, strong | ˈkøːʌ | køre | ˈsbœːʌ | spørge |

Imperative, strong | køʌ̯ːˀ | kør | sbœʌ̯ˀ | spørg |

Present tense, strong | ˈkøːʌ | kører | sbœʌ̯ˀ | spørger |

Past tense, strong | ˈkøʌ̯d(ə) | kørte | ˈsbuʌ̯d(ə), ˈsboʌ̯d(ə) | spurgte |

Perfect participle, strong | køʌ̯ˀd | kørt | sbuʌ̯ˀd, sboʌ̯ˀd | spurgt |

Present participle, strong | ˈkøːʌnn | kørende | ˈsbœʌnn | spørgende |

Some of these have stem-alteration in the past tense and the perfect participle, and therefore it is often the “stød” that shows the difference between the two forms (for more, see Sounds).

The suffixes in group 2 are:

Suffixes in speech | Suffixes in writing | |

Infinitive, strong | No suffix | -e |

Imperative, strong | No suffix | No suffix |

Present tense, strong | -ʌ | -er |

Past tense, strong | -d(ə) | -te |

Perfect participle, strong | -d | -t |

Presen participle, strong | -nn | -ende |

gøre “do” | lægge “lay” | |||

Speech | Writing | Speech | Writing | |

Infinitive, strong | ˈɡœːʌ | gøre | ˈlɛɡ(ə) | lægge |

Imperative, strong | ɡœʌ̯ˀ | gør | lɛɡ | læg |

Present tense, strong | ɡœʌ̯ | gør | ˈlɛɡʌ | lægger |

Past tense, strong | ˈɡjoːʌ | gjorde | ˈlæː(ː) | lagde |

Perfect participle, strong | ɡjoʌ̯ˀd | gjort | lɑɡd | lagt |

Present participle, strong | ɡœːʌnn | gørende | lɛɡnn(ə) | læggende |

In group 3 the verbs are often different in the past tense and in the perfect participle.

The suffixes of group 3 are:

Suffixes in speech | Suffixes in writing | |

Infinitive, strong | No suffix | -e |

Imperative, strong | No suffix | no suffix |

Present, strong | -ʌ | -er |

Past, strong | Often just vowel lengthening | -de |

Perfect participle, strong | -d | -t |

Present participle, strong | -nn | -ende |

The strong verbs are those that do not have any suffixes in the past tense. Most of them have vowel change in the past tense and in the perfect participle. The stød also changes with the different forms. We will limit ourselves two four examples here:

drikke ‘drink’ | tage ‘take’ | |||

Speech | Writing | Speech | Writing | |

Infinitive, strong | ˈdʁɛɡ(ə) | drikke | tæˀ, | tage |

Imperative, strong | dʁɛɡ | drik | tæˀ, | tag |

Present tense, strong | ˈdʁɛɡʌ | drikker | tɑˀ | tager |

Past tense, strong | dʁɑɡ | drak | toˀ | tog |

Perfect participle, strong | ˈdʁɔɡð/ | drukket | tæː(ː)ð | taget |

Present participle, strong | ˈdʁɛɡnn | drikkende | tæː(ː)nn | tagende |

Stå ‘stand’ | Komme ‘come’ | |||

Speech | Writing | Speech | Writing | |

Infinitive, strong | sdɔˀ | stå | ˈkʌmm | komme |

Imperative, strong | sdɔˀ | stå | ˈkʌm | kom |

Present tense, strong | sdɒˀ | står | ˈkʌmʌ | kommer |

Past tense, strong | sdoð | stod | kʌmˀ | kom |

Perfect participle, strong | sdɔːð, | stået | ˈkʌmmð, | kommet |

Present participle, strong | sdɔːnn | stående | ˈkʌmmn | kommende |

The suffixes are:

Suffixes in speech | Suffixes in writing | |

Infinitive, strong | -(ə) / no suffix | -e / no suffix |

Imperative, strong | no suffix | No suffix |

Present tense, strong | -ʌ / no suffix | -er/-r |

Past tense, strong | no suffix | no suffix (often vowel alteration) |

Perfect participle, strong | -ð | -et |

Present participle, strong | -nn | -ende |

Auxiliary verbs are verbs that go with a non-finite main verb. There are tense auxiliary verbs such as være ’be’ and have ‘have’; passive auxiliaries like være ‘be/have’ and blive ‘will be’ and modal auxiliaries such as kunne ‘could’, skulle ‘should/must’, måtte ‘must/may/could’ and burde ‘should’.

![SAMTALEBANK | SAM3 | GAMLEDAGE | 866 ((face-to-face)) 01 LIS: jam den er ikk kommet endnu yes.but it.C be.PRS not come.PPT yet 'yeah but it hasn’t arrived yet' 02 LIS: m[aden]↘ food.DEF 'the food' 03 KIR: [∙hhh] nej↘ (.) men den kommer lige straks→ no (.) but it.C come.PRS PTC right.away 'hhh no, but it’ll be here in a minute'](/fileadmin/_processed_/7/d/csm_verbs_5_16f1cb8d66.png)

Tense auxiliary verbs mark the tense of the main verb. In the example above er ’be/have’ acts as a tense auxiliary and, together with kommet ‘come (perfect tense)’.

In the example below the verb blir ‘will be’ acts as a passive auxiliary for the passive form angrebet ‘attacked’ in line 2:

The modal auxiliaries indicate the modality of the main verb, in other words, the way in which the main verb should be understood, e.g. hypothetically, wishing, possibility etc. In the example below the verbs må ‘may’ and ska ‘must’ act as modal auxiliaries. In line 3 må shows that it is allowed to call the emergency line in special circumstances. On the other hand, ska in line 5 indicates a norm or obligation i.e. an obligation not to call if it is not an emergency.

![SAMTALEBANK | SAM4 | MOEDREGRUPPEN0 | 1765 ((face-to-face)) 01 TAN: [ved akut akut ] nød at urgent urgent emergency 'in case of urgent, urgent emergency 02 et eller [andet] one.N or other.N 'or something' 03 DO: [akut ] nød 'urgent emergency' 04 DO: selvfølgelig må man så gerne [ringe] iggås↘ of.course may.PRS one then readily call PTC 'of course you are allowed to call then, you know ' 05 ?: [hcrm ] 06 DO: ∙hhh men ellers så ska man altså but else then must.PRS one PTC 07 ↓la vær med det→ let be.PRS with it.N 'but if not you shouldn’t do it'](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/6/csm_verbs_7_b9e4767ab5.png)

Tense and passive auxiliaries are some of the most frequently used verbs in talk-in-interaction. They can all occur both as auxiliary verbs and as main verbs. When they occur as auxiliaries they are normally unstressed, whereas if they occur as the main verb they are stressed. Therefore, we show them in both weak and strong forms below:

Stress | være ‘be’ | have ‘have’ | blive ‘become’ (and for passive) | |

Infinitive | Strong | ˈvɛːʌ | hæˀ | ˈbliː |

Weak | vɛʌ | hæ | bli | |

Imperative | Strong | vɛʌ̯ˀ | hæˀ | bliˀ |

Weak | vɛʌ̯ | hæ | bli | |

Present tense | Strong | æʌ̯ | hɑːˀ | bliʌ̯ˀ |

Weak | æ, lengthening of preceding vowel | hɑ, ɑ, lengthening of the preceding vowel | bliʌ̯ | |

Past tense | Strong | vɑ | ˈhæːð | bleˀ, blewˀ |

Weak | vɑ | hæð | ble, blew | |

Perfect participle | Strong | ˈvɛːʌð/ ˈvɛːʌd | hɑfd | ˈbleː(ː)ð/ ˈbleː(ː)d/ ˈbleːwn/ˈbløː(ː)ð |

Weak | vɛʌð/vɛʌd | hɑf(d) | bleð, bled, blewn, bløð | |

Preset participle | Strong | ˈvɛːʌnn | hæːwnn | bliːwnn, bliːnn, |

The stems of the auxiliary verbs are:

There is a consistent difference between the spoken forms of the auxiliary verbs kunne ‘could’, skulle ‘should’, ville ‘would’, måtte ‘may’ and the written forms of the same verbs. The modal verbs do not exist in the imperative or in the present participle.

Here is an overview of the forms of the main modal verbs:

Stress | kunne ‘could’ | skulle ‘should’ | ville ‘would’ | måtte ‘may’ | |

Infinitive | Strong | ˈkun(n), ku | ˈsɡul(l), sgu | ˈvill | ˈmʌd(ə) |

Weak | ku, kʷ | sgu, sgʷ | vil, vi | mʌd | |

Present tense | Strong | kænˀ, kæn, kæ | sgælˀ, sgæl, sgæ | ˈvelˀ, vel, ve | mɔˀ |

Weak | kæ, k | sga, sgə, sg | ve | mɔ | |

Past tense | Strong | ˈkun(n), ku | ˈsɡul(l), sgu | ˈvill | ˈmʌd(ə) |

Weak | ku, kʷ | ˈsgu, sgʷ | vil, vi | mʌd | |

Perfect participle | Strong | ˈkun(n), ˈkun(n)d, ˈkun(n)ð | ˈsɡul(l), ˈsɡul(l)d, sgu | ˈvill, ˈvil(l)d | ˈmʌd(ə)ð, ˈmʌdð |

weak | ku, kʷ | sgu, sgʷ | vil, vi | mʌd |

The modal auxiliaries have their short form in the present tense, as opposed to the strong verbs of group 4 which have it in the past tense. Furthermore, their infinitive form is identical to the past tense. In our data the short forms of these verbs are the most commonly used, which is also true for the stressed verbs. The difference between the presence or absence of stød in the stressed forms of the verbs may be regiolectally conditioned.

The verbs of talk-in-interaction are placed differently depending on their inflection, but the placement often corresponds to that of written language:

Most often verbs do not occur by themselves in a turn, but when they do it is often as a repair or as an imperative. In the following example the imperative of se ‘see’ constitutes a single turn:

We have not found an example of a separate verb working as repair in our data, but here is an experienced example written down from memory:

In the example above a separate verb in line 2 points to a problem in the previous utterance, and is then corrected by another separate verb in line 3.

Turns-at-talk can also omit verbs all together. That often happens in response-turns to e.g. a yes/no-question, but in lines 12, 13 and 14 below the verb-less utterances act as meaningful contributing units in and of themselves.

According to the grammar of written language, line 14 lacks the copula verb er ‘is’ after det ‘that’. But our data suggests that the Danish copula is often assimilated with the previous pronoun (see more under Copula drop). On the other hand, line 13 is characterized by the obvious absence of any verb. This shows that verbs of talk-in-interaction are not always necessary in order to create meaningful units.

Christensen & Christensen (2014) is a textbook that builds on a long tradition of grammatical description.

Grønnum (2005) is a thourough description of Danish phonology, including stress and prosody.

Hansen & Heltoft (2011) is a major, thourough and scientific description of Danish grammar. It contribues to many areas following traditions in descriptive grammar, but it does not have a systematic treatment of talk-in-interaction.

Monrad (2016) is an overview of the systematics of the pronunciation of many frequent Danish verbs.

Nissen (2015) has examples of verbs (and other words) standing alone as repair.